Angels of Bataan

US Army and Navy

WWII POW Nurses

Malinta

Tunnel Hospital

Corregidor Island, Philippines |

|

|

In the autumn of 1941, the

Philippines was a gardenia scented paradise for the American Army and

Navy nurses stationed there. War was a distant rumor, life a routine of

easy shifts and dinners under the stars. On December 8 all that

changed, as Imperial Japanese bombs began raining down on American

bases in Luzon, just ten hours after the attack on Pearl Harbor, and

this paradise became a fiery hell. Caught in the raging battle, the

nurses set up field hospitals in the jungles of the Bataan Peninsula

and the tunnels of Corregidor Island, where they tended to the most

devastating injuries of war, and suffered the terrors of shells and

shrapnel. But the worst was yet to come.

After Bataan

and Corregidor fell, 66 US Army and 11 US Navy nurses were herded into

Santo Tomas University internment camp in Manila, capital city of the

Philippine Islands, the Navy personnel later being transferred to Los

Banos, where organized to continue to apply their medical skills for

all in the camps, they would endure three years of fear, brutality, and

starvation. Once liberated, all having survived the war, returned to an

America that at first celebrated them, but later denied them the

veterans benefits that they deserved. |

|

| April

11, 1942 US and Filipino Troops, Victims of Japanese Bombing Attacks on

Bataan Peninsula, Philippines, in Open Air Field Hospital After

Receiving Medical

Treatment |

|

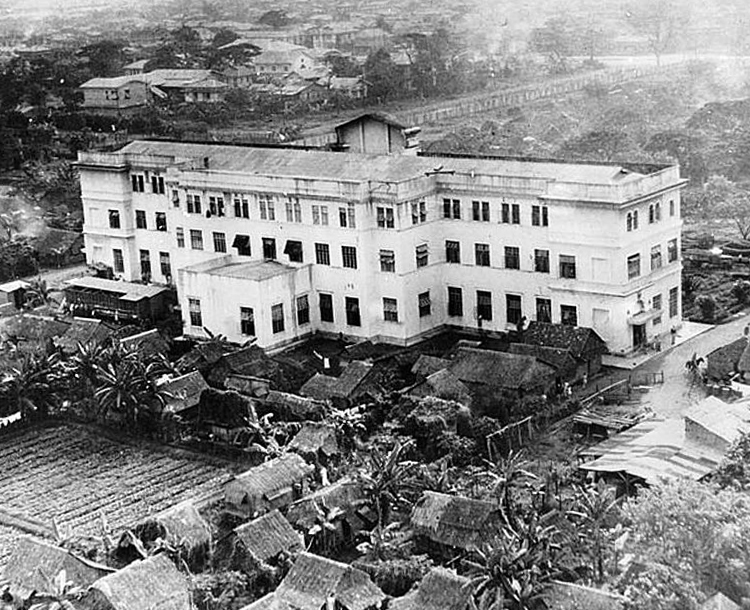

| Santo Tomas University, Manila Internment Camp |

|

| M4 Sherman Tanks Liberation of Santo Tomas 1945 |

|

On

the evening of February 3, 1945, a Sherman tank barreled its way

through the front gates of the University of Santo Tomas, in Manila,

Philippines. The tank, a composite hull M4 Sherman named the “Battlin

Basic” by its crew, belonged to Company B of the U.S. 44th Tank

Battalion and was the first glimpse of liberation for over 4,000

civilians – mostly Americans and British citizens, including

Australians and Canadians – interned at the university from January

1942 to February 1945. Santo Tomas was the largest of several

internment camps established by the Japanese throughout the Philippines.

Santo Tomas Raid

By Peter R. Wygle*

One

of the most awe-inspiring yet historically little remembered missions

of World War II in the Pacific were the four rapid-fire prisoner of war

liberation raids in the Philippines. These four raids, Bilibid,

Cabanatuan, Santo Tomas, and Los Banos, all took place in a one-month

period between late January and the end of February, 1945, and the men

who planned them faced many of the elements of potential failure; the

raids, with the exception of the Bilibid liberation in Manila, were

independently planned in very restrictive time-frames by at least three

different headquarters; they involved every branch of the American

military, with enormously important help from, and sacrifice by, the

Filipino people and their guerrilla Army; and they employed practically

every method of attack and means of transportation known to man. In

spite of all this potential for confusion and failure, each of the

rescues was pulled off without a hitch. These prisoner raids –

collectively – killed, wounded, or scattered about a thousand enemy

troops and resulted in freedom for almost eight times that many allied

prisoners of war, including the largest number of American civilian

internees ever taken prisoner by an armed enemy in the history of our

nation. All of this while sustaining relatively light – though

certainly not insignificant – casualties among the American forces and

their supporting Filipino guerrillas.

MacArthur

Impressed

Legend

has it that General MacArthur was so impressed by the Cabanatuan raid

by elements the 6th Ranger Battalion – which was still in progress at

the time – that he went immediately to MG Mudge’s 1st Cavalry Division

headquarters in Guimba. There he ordered the formation of a ‘Flying

Column’ to accomplish the same thing with the 3,700 civilians interned

at the University of Santo Tomas in Manila. Nobody knew about the 1,300

or so military and civilian prisoners at the old Bilibid prison which

was only a few blocks from Santo Tomas.

The oratory attributed

to the general during this conference was typically MacArthur: “Go to

Manila! Go over the Japs, go around the Japs, bounce off the Japs, but

go to Manila! Free the prisoners at Santo Tomas and capture Malacanang

Palace and the legislative buildings.”

Two-thirds of this

grandiose mission was practicable from where the 1st Cavalry Division

sat. Santo Tomas and Malacanang Palace were in the north end of Manila,

the same side that the 1st Cav was on, but the legislative buildings

were on the south side of the Pasig River. This large river runs

east-to-west through the middle of Manila and there were only three or

four bridges across it. The chances of the Japanese destroying the

bridges and turning the river into a major obstacle were pretty good.

If the Japanese managed to do this, it would make the legislature

buildings relatively hard to reach.

The

‘Flying Column’

When

MacArthur decreed the formation of the ‘Flying Column’ the 1st Cav

troops, to whom he had decreed it, had come ashore at Lingayen Gulf on

27 January, 1945 after 72 days of continuous combat in the mountains of

Leyte, and the division had just completed its move 35 miles south from

Lingayen to Guimba, arriving there on the 30th. As fierce as the combat

on Leyte had been, the memory that usually gets shared by the 1st Cav

Troopers that were there is the fact that during 40 of those 72 days,

35 inches of rain fell. The Troopers had earned some rest, but there

was to be none. They received “MacArthur’s Flying Column” decree on the

day after they arrived at Guimba. MG Mudge spent the rest of the 31st

gathering the troops he thought it would take to accomplish his new

mission. These troops included, in addition to parts of the 5th Cavalry

and 8th Cavalry Regiments and some miscellaneous support people, the

44th Tank Battalion, a bunch of air cover from Marine Group 24 and 32

and – luckily – a Navy demolitions expert, Lieutenant (JG) James

Patrick Sutton. MG Mudge divided the Column into three serials,

assigning missions to each, and, at one minute past midnight on the

morning of 1 February, 1945, led them out of Guimba. The race to Manila

was on!

The Column, carrying only four days’ rations and the

absolute minimum in arms, ammunition and fuel, had to tread carefully

for the first few miles because the Cabanatuan prisoners were still

being evacuated across its path. Once in the clear, however, it fought

its way at top speed down Highway 5, slowing for a day of heavy

firefights at Cabanatuan and Gapan. An ambush at a road intersection

during the fight at Gapan cost the life of LTC Tom Ross, commander of

the third serial. This was the serial with most of the 44th Tank

Battalion assigned to it.

After this fierce early fighting the

Column sped south, depending totally upon the Marine flyers for flank

security. The 1st Cav moved toward Manila, pausing only to bypass blown

bridges and to engage the Japanese in hit-and-run fighting. It hit a

snag however, at the Novaliches Bridge just south of a road junction

that became known as “the Hot Corner”. They were still about ten miles

short of Manila.

Mines had been set, the fuse was lit, and the

Japanese were laying down heavy sniper fire on the bridge to discourage

all efforts to prevent its destruction. Bypassing this particular

bridge was not an option because the gorge was deep and the river was

swift. It was here that having Pat Sutton along turned out to be a

stroke of good fortune. He, apparently protected by some sort of a

providential force field that seemed to repel sniper bullets, ran out

on the bridge and cut the demolition fuse, enabling the Column to cross

the river with dry feet.

LT Sutton also helped in clearing a

path through a minefield further south on the approach to Manila. His

next running – with his brand new Distinguished Service Cross – was for

Congress where he won a Tennessee seat in the House of Representatives.

After

the Column crossed the river at Novaliches it moved down Quezon

Boulevard straight toward Santo Tomas Internment Camp and Malacanang

Palace.

Inside

the Prison Camp

Inside

the prison camp, 3,700 apprehensive civilian men, women and children

were watching the approach of the tracer-bullet fireworks in the

evening sky with a strange mixture of excitement and dread. After three

years in the “protective custody” of the Japanese Army, they were

excited that SOMETHING was happening – even if they didn’t know what it

was – but mixed in with this excitement was dread of the possibility

that the pyrotechnic display was, in truth, being caused by the bad

guys headed their way with malice in their souls. Rumors had been

rampant for some time that the Japanese intended to kill all of their

prisoners.

Late on 3 February, 1945, after a couple of wrong

turns and some heavy fighting in the mixed-up outskirts of Manila, the

Santo Tomas column picked up CPT Manuel Colayco, a Filipino

newspaperman and clandestine intelligence officer, who guided them to

the main gate of the prison camp. At about nine in the evening, after a

brief flurry of resistance by the Japanese guards during which CPT

Colayco was fatally wounded by a grenade explosion, the 44th Tank

Battalion’s M-4 Sherman “Battlin Basic”, closely by the “Georgia Peach”

knocked down the gate and the war was nearly over for the internees.

The

Flying Column was 66 hours into its mission. With time out for the

fights at Cabanatuan and Gapan, and delays in bypassing some of the

blown bridges, it had covered 100 miles. The 1st Cav had toeholds –

tenuous as they might actually have been – at Santo Tomas and at the

Malacanang Palace.

Liberation

For

the Santo Tomas internees, their liberation was followed by a night of

delirious happiness, a standoff and hostage crisis in one of the campus

buildings, and two or three days of murderous artillery dueling.

The

artillery battle resulted when the few hundred men of the 1st Cav, not

having all that much Manila real estate under their control, had to set

up their artillery inside the Santo Tomas complex and begin making

enough noise to discourage thoughts of counterattack in the minds of

Admiral Iwabuchi and his twenty thousand marines defending Manila. The

good news was that no counterattack materialized; the bad news was that

the presence of American artillery in the front yard invited

counterfire from the Japanese, and the internees were in the middle.

This several day artillery duel caused the only prisoner causalities of

the Santo Tomas liberation – with the possible exception of a couple of

internees who reportedly ate themselves to death in the first day or

so. Seventeen internees and several 1st Cav Troopers were killed in

this exchange of fire and many more were injured.

After the

shooting died down, only a couple of months of stomach aches from the

unaccustomed good food and headaches from the seemingly endless

interminable processing stood between the ex-prisoners and, for many of

them, repatriation.

*This is an excerpt from a paper by Peter R.

Wygle entitled “Jeb Stuart Would Have Loved It!” that covers the four

mentioned POW camps. Pete Wygle was a civilian internee at the Santo

Tomas Internment Camp, a boy of about ten or 11 years old at the time.

He also authored the book, “Surviving a Japanese POW Camp”, served on

active duty in Korea and later in the Army National Guard retiring as a

Colonel. He was also very active in the American Ex-Prisoners of War

Association. Pete died of cancer in September 2003. Pete’s widow,

Nancy, graciously provided a copy of this paper for inclusion in the

1st Cavalry Division Museum archives. Edited for publication in SABER

by Robert W. Tagge, Member of the Board of Governors, 1st Cavalry

Division Association and Executive Director of the 1st Cavalry Division

Museum Foundation.

US

Marine Corps Douglas SBD Dauntless Close Air Support

US

Marine Corps Douglas SBD Dauntless Close Air Support

Fortunately,

on 31 January Gen MacArthur gave MAGSD opportunity to prove the utility

of Close Air Support. General MacArthur ordered the 1st Cavalry

division to make an audacious advance of 100 miles to Manila and free

the internees at Santo Tomas. The assignment of MAGSD was a unique

mission of guarding the 1st Cavalry Division flank with a standing nine

plane patrol from dawn until dusk. With some "superior salesmanship and

a determination to show the soldiers what Marine flyers, under proper

front line control could do for them," the MAGSD was able to attach two

Marine Air Liaison Party (ALP) jeeps to follow the 1st and 2nd Brigades

of the 1st Cavalry. The standing nine plane patrol reconnoitered ahead

of the flying column spotting the Japanese positions and routing the

forces around ambushes.

On 2 February 1945, a portion of the Cavalry

was blocked by a Japanese battalion which occupied a ridge that was

reported to withstand an entire division. The attached ALP was able to

call the SBD patrol to complete multiple shows of force and allowed the

Cavalry to route the Japanese without the SBDs firing a shot. The same

day the SBD patrol completed an ad-hoc bombing run ahead of the 1st

Cavalry line in which all bombs landed within a 200 by 300-yard area

and left the target in shambles. Finally, the ALP demonstrated the

increased speed of communication when a Regimental commander dashed to

one of the MAG ALP jeeps to report a Japanese fighter in the area. An

officer in the ALP pointed to a burning fighter 2,000 yards away which

had been destroyed by two P-51s the ALP had vectored in. Within 66

hours the 1st Cavalry arrived in Manila, and the Marines of both MAG-24

and MAG-32 had proven their ability to make the innovative changes in

Close Air Support work. The MAGs received commendations from both the

Brigades and the CG of the 1st Cavalry. However, the division historian

summed up the Marines contribution the best: "Much of the success of

the entire movement is credited to the superb air cover, flank

protection, and reconnaissance provided by Marine Air Groups

24 and

32."

|

US

Army Nurses Liberated February 3, 1945 |

| The

Battle of Manila, which raged throughout the month of February 1945,

cost the lives of over 100,000 Filipinos and completely destroyed

Manila, considered one of the most beautiful cities in the world at the

time and commonly referred to as the Pearl of the Orient. According to

General MacArthur, next to Warsaw, Manila was the most devastated city

in WWII. It is ironic that whereas Hitler’s order to burn Paris went

unheeded, thereby saving Paris, General Yamashita’s command to leave

Manila without defending it, which would have saved the city, was also

disobeyed, but with contrasting and devastating consequences. Yamashita

was tried at the U.S. High Commissioner’s Residence – now the U.S.

Embassy in Manila – and later hanged for war crimes. |

Los

Banos Internment Camp Rescue

|

| US Navy Nurses Liberated February 23, 1945 |

|

| LVT-4, Landing Vehicle Tracked (Amtrac) |

|

| Amtrac Amphibious Assault Vehicles |

|

| |

|

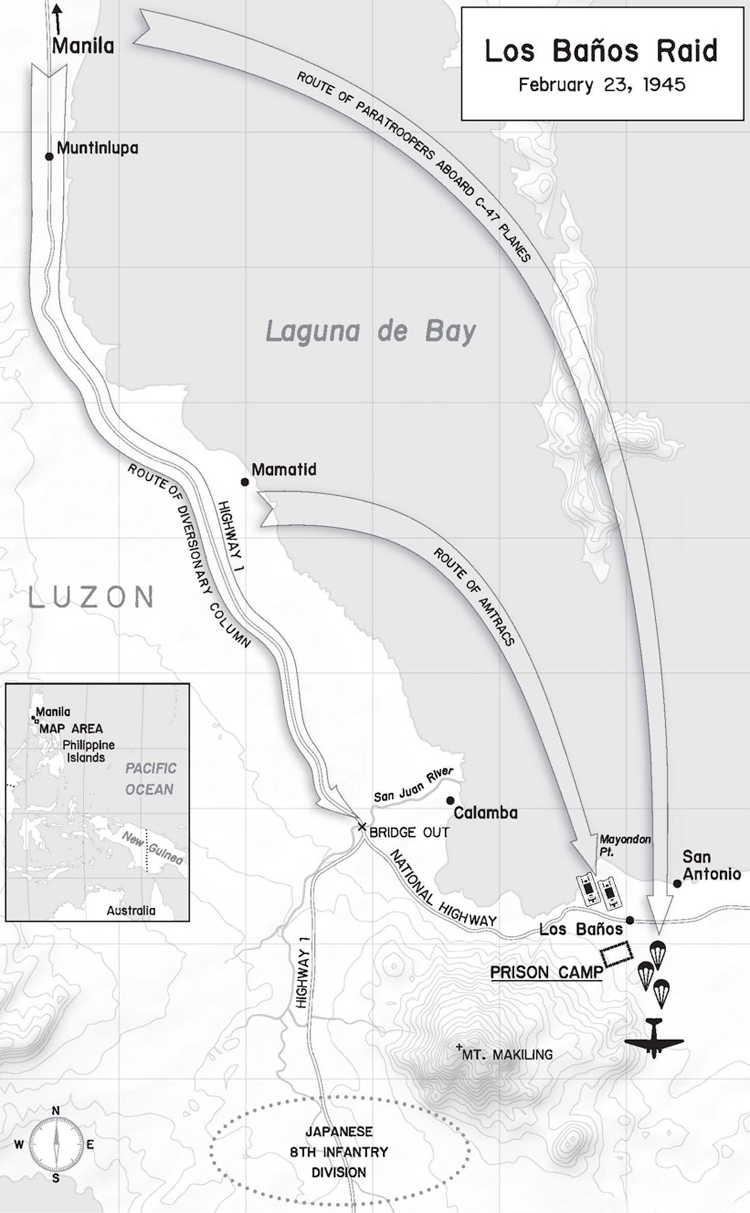

The

civilian internment camp near Los Banos had been established by the

Japanese in December 1942 at the Agricultural College of the University

of the Philippines, located about 2 1/2 miles southeast of the town.

Held within the large, fenced compound of more than 30 buildings were

2,147 internees of various nationalities, including 1,575 Americans.

The raid on

Los Banos, located 40 miles behind Japanese lines

would entail a four-pronged attack. The 511th PIR Provisional

Reconnaissance Platoon under Lieutenant George E. Skau, aided by local

guerrillas, would move into an area opposite the camp prior to the

strike. Then, simultaneous with a parachute drop of Lieutenant John M.

Ringler’s Company B of the 511th PIR and an amphibious landing by Major

Henry A. Burgess’s 1st Battalion, minus the airdropped company but

reinforced with a platoon from C Company, 127th Airborne Engineer

Battalion and two howitzers from Battery D, 457th Parachute Field

Artillery Battalion, the recon platoon and guerrillas would eliminate

the sentries along the wire.

While the amphibious force, landing

in LVT-4 amphibious tractors or amtracs of the 672nd Amphibious Tractor

Battalion rolled up onto the beach from Laguna de Bay and continued

toward the camp, the company of paratroopers would link up with the

recon platoon and guerrillas and wipe out the rest of the garrison.

When the amphibious force reached the camp, it would deploy to the

south and west to block any reaction by the Japanese.

The fourth

force would form a flying column composed of the 1st Battalion, 188th

Glider Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lt. Col. Ernie LaFlamme, the

675th Glider Field Artillery Battalion, the 472nd Glider Field

Artillery Battalion, and Company B of the 637th Tank Destroyer

Battalion and move by road around the southwest end of Laguna de Bay up

to the gates of the camp. This force, under the command of Lt. Col.

Robert H. Soule and designated “Los Banos Force,” would bring enough

trucks with it to carry out all the internees and paratroopers. If the

fourth group could not reach the camp, the internees could be ferried

out in the amtracs across Laguna de Bay while the paratroopers fought

their way out. The raid was scheduled for dawn on February 23, 1945, a

moonless night. |

|

| Liberated US Navy Nurses with Admiral Kincaid |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| |

|

| Liberated US Army Nurses Receive Bronze Star Medals |

|

| |

|

We

Band of Angels

Elizabeth Norman |

In

December 1941, American bases in the Philippines were caught in a

raging battle when Japanese forces attacked. Nurses set up field

hospitals in the jungles of Bataan and the tunnels of Corregidor, where

they tended to the most devastating injuries of war. They later endured

three years of fear, brutality and starvation in internment camps.

Once

liberated, they returned to an America that at first celebrated them,

but later refused to honor their leaders. Norman reveals the letters,

diaries and riveting firsthand accounts that explain what really

happened during those dark days, woven together in a deeply affecting

saga of women in war.

Elizabeth Norman is a professor at New York University’s Steinhardt

School of Culture, Education, and Human Development. She is the author

of “Women at War: The Story of Fifty Military Nurses Who Served in

Vietnam 1965-1973”, “We Band of Angels: The Untold Story of American

Women Trapped on Bataan by the Japanese” and co-author with her

husband, Marine Corps Veteran and former New York Times reporter,

Michael Norman of “Tears in the Darkness: The Story of the Bataan Death

March and Its Aftermath”. The book was on the New York Times

best-seller list for nine weeks and a Dayton Literary Peace Prize

finalist.

Norman’s awards include the American Academy of

Nursing National Media Award, The University of Virginia Agnes Dillon

Award, a Certificate of Appreciation from the Embassy of the

Philippines in Washington, D.C. and an Official Commendation from the

Department of the Army for her military research. |

| |

| Angels of Bataan Films |

|

Donna

Reed and John Wayne

They Were Expendable 1945 |

| US

Army Nurse cares for wounded in Malinta Tunnel on Corregidor Island,

the Philippines

after Imperial Japanese attack and before transfer to Bataan Peninsula. |

|

Claudette

Colbert

Paulette Goddard

Veronica Lake

So Proudly We Hail 1943 |

| At

the start of World War II in the Pacific, Lieutenant Janet Davidson

(Claudette Colbert) is the head of a group of U.S. military nurses who

are trapped behind enemy lines in the Philippines. |

|

Landing Vehicle Tracked

LVT Tour

US Marine Corps

1952 TV Program

Written by Member of the

Last China Band,

WWII POW, and Bronze Star Medal

with "V" Device Recipient,

First Lieutenant George Francis, USMC, Retired

80 Years Since Attack on

Pearl

Harbor and the Philippines

December 7, 2021 |

|

| Last China Band Digital Card |

Copy and paste to a text or email.

Below is a printable version

with eighth inch trim edges: |

Last_China_Band

Business_Card.pdf |

|

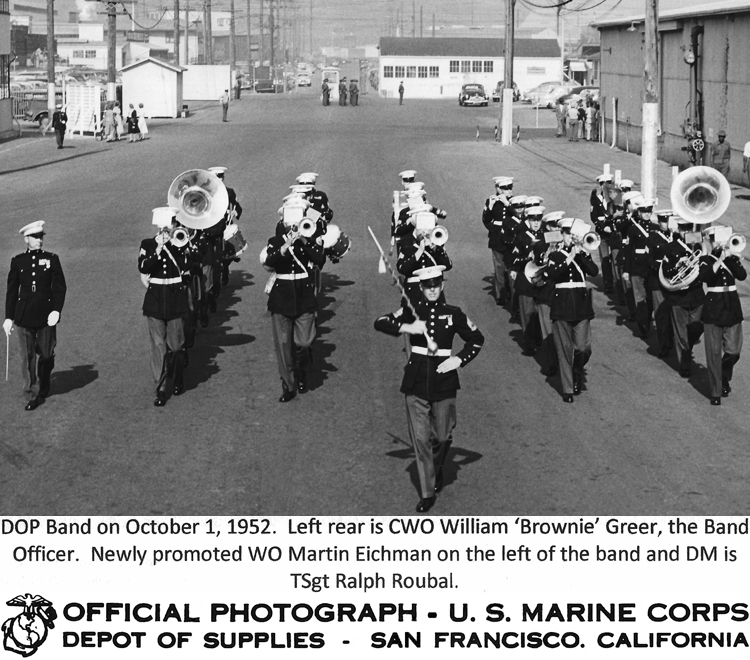

Last

China Band Members and Former World War II Prisoners of War Martin

Eichman, Jack P. Rauhof, Kenneth Marshall and Other Late 1940's and

1950's USMC Bands Original Photo Prints from Third Marine Aircraft Wing

Band, 3rd MAW, Miramar Marine Corps Air Station, San Diego, CA and

Marine Corps Musicians Association Historian

Band Photos After WWII

Miramar 3D MAW Band

|

| Please Click Below For: |

| Return

to Additional Photos Page |

| |

Return

to Books / Photos Page

EMAIL:

info@4thMarinesBand.com

714-227-5741

©2000-2023 LastChinaBand.com

All rights reserved. |

|