|

|

|

| Fourth Marines Band: "Last China Band" |

|

Marine Detachment, Air Warning Service |

|

Richard A. Long |

|

| Radar, the Word Still Classified, First Combat Uses by US at Pearl Harbor and Manila Bay |

|

| US Curtiss P-40 Warhawk Fighter Strikes Back at Imperial Japanese Navy Dive Bomber |

|

| Imperial Japan Attack on US at Cavite Navy Yard, Manila Bay, Philippine Islands |

|

|

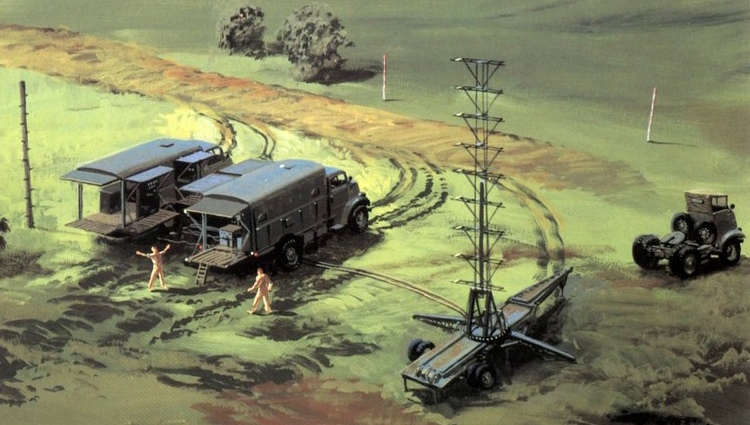

| The 1st Separate Marine Battalion at Cavite

provided antiaircraft and ground protection for all naval activities

there. It manned three 3-inch, .50-caliber batteries; one 3-inch,

.23-caliber battery; and two .50-caliber machine gun batteries. When

necessary, enough men could be mustered to provide infantry protection

for the Navy Yard, the Naval Air Station and Hospital on Sangley Point

and the Naval Air Base at Los Banos. What is not commonly known, for great secrecy appears to have surrounded the matter, is that the battalion’s communications unit had equipment with the capability to intercept aircraft by “radio detection.” Its acronym, “radar,” would not be freely spoken of in military circles until early in 1943. Marine Lieutenant Colonel Howard L. Davis, at that time a captain and battalion communications officer, stated in 1956 that three radar sets had been received at Cavite in November 1941. Two were SCR-268s, short-range sets designed to be electronically coupled to Mark IV fire control directors and thence to searchlight batteries and antiaircraft batteries for effectively controlled fire on enemy aircraft. Unfortunately, the battalion had no fire control directors. These sets were subsequently used for training additional personnel at Cavite. The third set, a long-range mobile SCR-270B, was designed for early air warning, capable of computing distance and azimuth, but not altitude, of aircraft. It had been planned to connect the detachment by a radio network to the Army Air Corps Air Warning Service facility at Nichols Field. Its detachment was made up of a few trained technicians and a majority of security and service personnel. Warrant Officer John I. Brainard, who arrived in Cavite in mid-November 1941, commanded the detachment. Master Technical Sergeant Clarence L. Bjork, an electronics expert, had reported for duty only two months earlier. Private First Class Irvin C. Scott, Jr., one of six enlisted Marines chosen from the 1st and 2d Defense Battalions in San Diego to attend a formal course in radar at the U.S. Army’s Signal Corps School at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey, in 1940 and 1941, was the detachment’s lone trained oscilloscope operator. However, in a short time he had partially trained two other Marines to spell him in coming months in the closed and secluded operator’s van. The unit’s comings and goings within a guarded enclosure next to Cavite’s quartermaster supply at the Marine Barracks were a mystery to its fellow Marines. On 4 December, Gunner Brainard moved his 36-man detachment and one Navy corpsman into the field, borrowing trucks and tractors from a Philippine Army unit to tow heavy power and scope vans and one antenna trailer to Wawa Beach near Nasugbu in Batangas Province, about 100 miles south of Cavite. Here, the detachment was placed under the direction of then-Colonel Harold H. George, U.S. Army Air Corps, commanding the V Interceptor Command, U.S. Army Forces in the Far East (USAFFE), for training and to augment the aircraft warning network covering Luzon. The unit remained in place following the news that Pearl Harbor had been attacked, technical personnel maintaining a 24-hour watch over Manila Bay and the nearby China Sea. At mid-morning, 10 December 1941, Scott picked up on his screen an elongated blip unlike anything witnessed in recent training. Continual tracking brought about the startled realization that he had spotted a massive airplane formation at approximately 120 miles to the southwest, approaching Manila Bay. Attempts to raise the Sangley Point towers on the radio were futile. When the duty radioman did succeed in reaching Army Radio on Corregidor, operators there, having never heard of radar, exasperatingly refused to acknowledge the transmission or to pass the sighting on to higher headquarters. Cavite was subsequently bombed into near rubble by succeeding waves of 54 Japanese bombers. Marine antiaircraft fire was for the most part ineffective, for the aircraft were beyond its range. More than 400 Marines, sailors and Filipino workmen were killed or wounded. The effectiveness of Cavite as a provider of support to the U.S. Fleet was brought to an end. Realizing that the position on Wawa Beach was now insecure, Brainard moved his radar inland several miles, near a sugar cane refinery, taking advantage of adjacent natural jungle cover to camouflage his vehicles and equipment. His caution was rewarded, for several nights later some of his security riflemen who kept a vigil on the beach surprised a seaborne Japanese scouting party looking for the radar emplacement there. This sole Marine long-range radar became even more precious, for on the opening day of the war in the Philippines, an identical Army unit at Iba Field, on the west coast of Luzon, was bombed out of existence. An Army emplacement at Aparri met the same fate, and another north of Legaspi was destroyed to keep it from falling into the hands of Japanese who landed there. Shortly thereafter, Colonel George sent three surviving soldiers from one of those units to join the Marine detachment. Meanwhile, few activities continued at Cavite. The Naval Hospital moved to Manila, submarines and supply ships departed, and surviving Marines established bivouacs in the barrio outside the base and at the radio station on Sangley Point. However, these were also destroyed in bombings of 19 and 20 December. The 1st Separate Marine Battalion moved to Mariveles on the tip of Bataan and on to Corregidor on 26 December, where on 1 January 1942 it was redesignated 3d Battalion, 4th Marines. Finding itself virtually isolated from allied organization, and in danger of being cut off by Japanese forces advancing on Manila from the southeast, the detachment evacuated its lonely site on Colonel George’s orders the day before Christmas. Despite having found only balky and antiquated alcohol-burning Filipino trucks, Brainard succeeded in extracting his secret cargo from the jungle in separate convoys past a nearly abandoned Cavite. The unit paused in Manila, now aflame and declared an open city, only to collect what extra supplies it could find. Two convoys were reunited in the courtyard haven of a Catholic church on the outskirts of San Fernando on Christmas Eve. Christmas dinner consisted of hardtack, cheese spread, and Ovaltine, the missing trucks containing the regular rations. On the following day, the power and scope vans joined the detachment at Orani, upper Bataan Peninsula, alongside Manila Bay. Brainard selected a well-camouflaged site in a mango grove at KM (kilometer) 148.5 between Orion and Limay and began operations. In the 31 days since the war began, the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress fleet had been partially destroyed, and the number of operational Curtiss P-40 Warhawk fighters was reduced to twelve. The Japanese had air superiority. Allied antiaircraft capability was desultory. The mission of the Marine Air Warning Detachment was changed from defensive to offensive. Allied aircraft sorties were carefully tracked, and any other blip on the radar screen was considered an enemy. U.S. pilots were advised and forewarned by radio to elude these enemy aircraft and their antiaircraft positions. The vagaries of war had orphaned the detachment. Although its personnel had been assigned to Headquarters Company of the 1st Separate Marine Battalion, that organization on Corregidor was now unable to render support. Army and Army Air Corps quartermasters were reluctant to logistically help them, and the Navy refused to supply a “detached” unit. Warrant Officer Brainard therefore directed select Marines to “reconnoiter,” or to scrounge for food, fuel, and other supplies the length of the peninsula. Their ingenuity was a wonder. In fact, chits signed by Brainard were issued to non-technical support troops to cover their far-ranging activities, as well as for several men to accompany Army tankers to the front lines as “observers.” However, three men were later court-martialed for plundering a foreign vessel disabled offshore but not completely abandoned. Five men joined Army Captain Arthur “One Man Army” Wermuth’s Filipino Scouts for night raids on Japanese positions, but Brainard put a stop to this after one Marine was killed and two wounded. These and other bold forays earned the Marine Air Warning Detachment the sobriquet “The Rogues of Bataan.” As a result, the Marine command on Corregidor sent First Lieutenant Lester A. Schade, Company L, 3d Battalion, 4th Marines, to Bataan on 17 January to relieve Brainard in command. Strictness reigned for a few days, until necessity brought back the need to acquire supplies. Brainard stayed on in a technical capacity. By the end of January Japanese advances in the II Army Corps area on the eastern half of Bataan placed the site of the detachment in jeopardy. Shells of 240mm artillery had straddled their position, and spotter aircraft were getting too close for comfort. They prepared to move again. Newly promoted Brigadier General George and his remaining pilots were flying mostly nocturnal missions with their P-40’s from the newly prepared Bataan and Cabcaben Fields just east of the barrio of Cabcaben. Brainard chose an elevated site near the flyers’ bivouac, on the northwestern edge of Bataan Field. They began operations there on 3 February, continuing the mission of informing American pilots when possible of encroaching enemy aircraft. In January 1992, Scott, a retired geologist now living in Richmond, Virginia, stated that one night in mid-March 1942 he was experimenting with the possibility of picking up surface traffic on Manila Bay and succeeded in following three American gunboats on patrol out of Corregidor. General George was elated and wanted to know if he could do it again. A few nights later he had the satisfaction of tracking a flotilla of small enemy vessels in the bay. Under cover of darkness and spewing a smokescreen, the Japanese were attempting an amphibious landing behind American lines. Scott detected them well out from the shoreline, and his prompt radio alert enabled pilots, Army artillery in the vicinity, and the Navy’s gunboats to repulse the enemy. No landing was effected. A massive Good Friday assault by the Japanese coupled with a general collapse of American and Filipino lines due to high casualties, battle fatigue, epidemic disease, and short rations, resulted in the final evacuation of the Marine radar unit. Orders received on 8 April directed them to get their equipment and troops to the docks at Mariveles for transfer to Corregidor. However, on reaching the cut-off road from the East to West Road and within sight of their destination, several factors brought about their disintegration. First, a tremendous earthquake rocked the entire peninsula, followed by the Navy and Army blowing up ships, ammunition, fuel, and other supplies stored in tunnels and in the open. Japanese bombers contributed to the confusion, bombing and strafing service facilities and hospitals, as well as a mass of equipment and humanity streaming toward the port on all roads and trails. Finding their path effectively blocked and the last of the major vessels capable of transporting their radar, men, and equipment already departed, Brainard directed that the power, scope, and antenna carriers be properly primed, charges placed, and set afire. Other organizational vehicles were backed over a cliff onto rocks and surf below. Pandemonium reigned. Lieutenant Schade released the men from the unit, each to seek his own means of escape. Four men had been transferred to Corregidor on 4 April. An additional five, some together and the others singly, made their precarious ways to “The Rock,” where they joined the 4th Marines. A few, including Scott, could neither escape northward, nor find the means to cross the channel. They were gathered together at the shore by an Air Corps lieutenant who led them to an assembly area, fed them, and promised that a boat was to be sent from Corregidor. After destroying their small arms, they found to their dismay that the lieutenant was acting under orders to surrender them to the enemy. The following morning, the Japanese marched in and prepared them for what was later to be notorious as the “Bataan Death March.” |

|

|

|

Sources |

| The capture and subsequent loss in 1942 of the

original 4th Marines’ records prove at first daunting to any researcher

of the period. The search for source material must begin with part IV

of LtCol Frank 0. Hough, Maj Verle E. Ludwig, and Henry I. Shaw, Jr.’s

History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II, vol 1, Pearl

Harbor to Guadalcanal (Washington: HistBr, G-3 Div, HQMC, 1958). This

work proved to be the single best account of the regiment in the fall

of the Philippines. Other works of value include Hanson W. Baldwin’s “The Fourth Marines on Corregidor,” Marine Corps Gazette, Nov46-Feb47; Louis Morton, The Fall of the Philippines, The War in the Pacific: United States Army in World War II (Washington: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1953). Also useful were James H. and William M. Belote, Corregidor: The Saga of a Fortress (NY: Harper and Row, 1967); Reports of General MacArthur, vols I and II (Washington: GPO, 1966); Carl M. Holloway, Happy, the POW, (Brandon, Mississippi: Quail Ridge Press, 1981); Donald Versaw, The Last China Band (Lakewood, California: Peppertree Publications, 1990); and William R. Evans, Soochow and the 4th Marines (Rogue River, Oregon: Atwood Publications, 1987). The 4th Marines records which were brought out from Corregidor by submarine or retrieved from the prison camps after the war are found in the geographical and subject files in the Archives Section, Marine Corps Historical Center. The Personal Papers Collection proved to contain valuable items, including the Thomas R. Hicks journals, which contain a daily record of events of the regiment. Also of use were the Reginald H. Ridgely papers, Curtis T. Beecher memoir, Floyd 0. Schilling papers, Cecil J. Peart papers, James B. Shimel papers, Carter B. Simpson memoir, Wilbur Marrs memoir, and the Charles R. Jackson manuscript. Many other articles written by Marine participants or about the 4th Marines in the defense of the Philippines were consulted for this work. The best sources, by far, for the 4th Marines experience in the fall of the Philippines are the survivors themselves. Capt Elmer E. Long, Jr., USMC (Ret) and CWO Gerald A. Turner, USMC (Ret), provided assistance in locating the surviving members of the “Old” 4th. More than 100 Marines have been interviewed as well as men from other services. |

| Return to World War II Photos Page |

| EMAIL: info@4thmarinesband.com |

| ©2000-2021 fourthmarinesband.com. All rights reserved. |