|

The Japanese Imperial General Staff was

Supremely confident that they could take the Philippines with little

difficulty— so confident that they did not even allot the whole of

their XIV Army to the job. At first it seemed that they were justified;

for their landings were only lightly opposed, and their troops advanced

rapidly against an untrained and ill-equipped enemy. But the siege of

Bataan, on which the American and Filipino forces planned to make their

last stand, disrupted their progress. Disease and hunger struck both

besiegers and besieged, and Japanese victory was delayed for three

months until they could bring up fresh reinforcements.

On July 22, 1941, with the acquiescence of the Vichy government, Japan

occupied naval and air bases in south-east Indochina, and to counter

this threat the armed forces of the Philippines were brought into the

service of the United States. On the same day—July 26—the US War

Department established a new command: the US Forces in the Far East

(USAFFE), based at Manila under the command of General Douglas

MacArthur, who was recalled to active duty.

By the first day of December 1941, the line troops in USAFFE comprised

ten infantry divisions, five coastal artillery units, two field

artillery regiments, and a cavalry regiment equipped with horses and a

few scout cars. The elite troops were the Scouts — highly trained

members of the cavalry and artillery regiments — and the 45th Battalion.

On Luzon (see map below) there were two army groups, the North and

South Luzon Forces. Major-General Jonathan M. Wainwright’s North Luzon

Force was the stronger: there were the 11th, 21st, 31st, and 71st

Infantry Divisions, the cavalry regiment, the 45th Battalion, and three

field artillery batteries. Brigadier-General George M. Parker’s South

Luzon Force stood in the area generally south and east of Manila, and

consisted of two infantry divisions and a battery of field artillery.

A Visayan-Mindanao Force, under Brigadier-General William F. Sharp, was

given the rest of the archipelago to defend. This force consisted of

three infantry divisions, and the remaining division, the US Army’s

Philippine Division, was positioned between North and South Luzon

Forces. The defence of the entry to Manila Bay and Subic Bay depended

on five small fortified islands and their garrisons, commanded by

General Moore.

Major-General Brereton commanded the US Air Force in the Philippines,

which was given the title of Far East Air Force. Brereton’s most useful

aircraft were the B-17s (Flying Fortresses) of Lieutenant-Colonel

Eubank’s 19th Bombardment Group. All but one of the fighter squadrons

in the 24th Pursuit Group were equipped with modern P-40s (Kittyhawks),

under the command of Brigadier Clagett. Within 80 miles of Manila there

were six airfields suitable for fighters and only one — Clark Field —

suitable for heavy bombers; and although there were seven radar sets in

the islands, only two had been set up by December. A makeshift system

of air-raid watchers communicated by the civilian telephone or

telegraph to the interceptor command at Nielson Field on the outskirts

of Manila. The two coast artillery anti-aircraft regiments protected

Clark Field’s B-17s and Manila with 3-inch and 37-mm guns, .50

machine-guns, and 60-inch Sperry searchlights.

The US Navy in the Philippines was based at Cavite, on the southern

shore of Manila Bay. Under Admiral Thomas C. Hart, the fleet consisted

of the heavy cruiser Houston, two light cruisers, 13 old destroyers, 29

submarines, six gunboats, six motor torpedoboats, miscellaneous

vessels, and an air arm of 32 PBY Catalinas.

Despite the inadequate training the infantry had received, the shortage

of air warning devices, and the lack of airfields, there was an

expression of optimism in Washington and in the Philippines that the

garrison could withstand an attack by the Japanese.

The Japanese Imperial Staff, however, was completely confident that

their XIV Army would conquer the Philippines within three months, and

that Luzon Island would be in their hands within 50 days. They based

their plan on a detailed knowledge of the American and Philippine

forces — their equipment, training standards, fighting ability, and

displacement. They were so confident that, instead of committing the

whole of the XIV Army, its commander, General Homma, was allotted only

two divisions, XVI and XLVIII, supported by two tank regiments, two

infantry regiments, and a battalion of medium artillery, five

anti-aircraft battalions, and various service units.

The Japanese V Air Group (army) and the XI Air Group (navy) were to

provide 500 bomber and fighter aircraft for the invasion.

At Formosa on December 1, General Homma received final instructions

from Southern Army Headquarters: operations would begin on the morning

of December 8 (Tokyo time). The air forces were to open the attack —

planned to coincide with the beginning of hostilities against Malaya—

soon after the raid was made against the American fleet in Pearl

Harbor. The Japanese Navy’s III Fleet, commanded by Admiral Takahashi,

was organised into numerous special task forces which comprised

transport and amphibious units supported by cruisers and destroyers. A

close cover force of three cruisers would support the main landings.

On Formosa, the experienced and highly skilled aircrews of the V Air

Group readied their Betty bombers and Zero fighters. Then at midnight

on December 7/8 a heavy fog closed in over the airfields, preventing

the scheduled take-offs at dawn. The Japanese commanders were filled

with nervous apprehension as they realised that the Americans on Luzon

would have news of the raid on Pearl Harbor and could, with the B-17s

of the Far East Air Force, attack the planes lined up on the Formosan

airfields.

All hope of surprise was lost.

|

|

| |

|

|

Japanese "Co-Prosperity" propaganda:

|

|

These match-box labels were part of the

constant Japanese attempts to turn the native populations of conquered

territories against the allies. the matches were circulated through the

normal trade channels, and were dropped on Allied-controlled territory

as well. Churchill and Roosevelt were main subjects of ridicule.

|

|

|

Caught on the ground

‘Air raid on Pearl Harbor. This is no drill.’ This was the dramatic

message tapped out from Hawaii at 0800 hours and received at the US

Navy Headquarters in Manila, where it was still dark and the time 0230

hours. A Marine officer passed the message to Admiral Hart, who

immediately advised the fleet. General MacArthur was not advised by the

navy but heard of the attack from a commercial broadcast shortly after

0330 hours. He then ordered the troops to battle stations.

The man most able to do something about an outbreak of war was General

Brereton at Clark Field, but he too only heard the news from a

commercial broadcast, and it was 0500 hours before he could reach

MacArthur’s office to seek permission to attack Formosa. Warned by a

telephone call from General Arnold in the US not to be caught with his

aircraft grounded and suffer the same fate as the anchored ships in

Pearl Harbor, Brereton sent the heavy bombers on patrol— but without

bombs — at 0800 hours. Eventually, at 1045 hours, orders were given for

two squadrons of B-17s to attack airfields on southern Formosa ‘at the

earliest daylight hour that visibility will permit’, and the patrolling

bombers were brought back to Clark Field to bomb-up and refuel. By 1215

hours the armed bombers and fighters of the 20th Pursuit Squadron were

lined up on Clark Field ready for take-off.

On Formosa, the fog had lifted enough by dawn to allow 25 Japanese army

bombers to take off for Luzon. At 0930 hours they were over north

Luzon, and attacked barracks and other installations at Tuguegarao and

Baguio without interference from American fighters. By 1015 hours, the

fog had further dispersed to allow the naval aircraft of the Japanese

XI Air Fleet to take off.

A force of 108 bombers, escorted by 84 fighters, arrived over Clark

Field at 1215 hours, achieving complete tactical surprise and catching

the US bombers and fighters, with their tanks full of fuel, perfectly

lined up for strafing runs. While anti-aircraft shells exploded 2,000

to 4,000 feet below them, two flights of 27 bombers accurately hit

aircraft, hangars, barracks, and warehouses, starting fires that spread

to the trees and the cogon grass around the field. The place became a

mass of flame, smoke, and destruction, and for more than an hour the

Zero fighters sprayed the grounded B-17s and P-40s with bullets. At the

Iba Field fighter base, another group of 54 Japanese bombers, escorted

by 50 fighters, destroyed barracks, warehouses, and the radar station.

Then Zero pilots found P-40s of the US 3rd Pursuit Squadron circling to

land at Iba:

all but two were shot down.

In the first few hours of the war in the Philippines, the Japanese

airmen had therefore achieved success beyond all expectation. For the

loss of seven Zeros, they had destroyed 17 B-17s, 56 fighters, some 30

miscellaneous aircraft, and damaged many others, while important

installations had been blasted or burned, and 230 men killed or

wounded. That afternoon, the US Far East Air Force had ceased to be a

serious threat to the invaders.

It is doubtful that even if the Far East Air Force had been spared on

the first day of war it would have survived for very long, and if the

bombers had raided Formosa it is doubtful if many of them would have

returned after a meeting with swarms of Zeros. Losses at Clark Field

would have been less had there been sufficient warning; but there had

been none. Nielson Field was advised of the approaching Japanese, but

the two squadrons that took off covered Manila and Bataan while Clark

Field was shattered.

The following day the invaders continued their preliminary tactics of

destroying air and naval power, attacking Nichols Field to hit aircraft

and ground installations. The next day, December 10, a two-hour attack

in the Manila Bay area was made on the Del Carmen Field near Clark, the

Nichols and Nielson Fields near Manila, and on the Cavite naval base

south of the city. At Cavite the entire yard was ablaze after the first

wave of 27 bombers accurately dropped their loads in the target area.

Repair shops, warehouses, the power plant, barracks, the dispensary,

and the radio station received direct hits. Casualties amounted to some

500 men. The submarine Sealion received a direct hit and a store of

over 200 torpedoes was lost. Fortunately, about 40 merchant ships in

the bay were unscathed and eventually escaped from the island. As a

result of the raid Admiral Hart ordered away two destroyers, three

gunboats, tenders, and minesweepers, planning to continue submarine and

air operations ‘as long as possible’.

Another Formosan fog made December 11 a quiet day but the next day over

100 bombers and fighters swarmed over Luzon, attacking any suitable

target without much fear of retaliation: by now the Americans had less

than 30 serviceable aircraft left. Seven PBYs were shadowed as they

returned from a patrol and were shot down as they approached to alight

on the bay. The next day the raiders numbered almost 200. On December

14 Admiral Hart sent the remaining PBYs south to sanctuary; on December

17 the intact B-17s were sent 1,500 miles away to Darwin in northern

Australia.

By now the Far East Air Force ceased to exist as a fighting force.

Except for a few patched fighters, the army was without air cover and

the navy was forced to rely mainly on submarines to protect the

thousands of miles of beaches against hostile landings — which had

already begun on the northern coast of Luzon.

|

Philippine

Island of Luzon |

|

| |

|

|

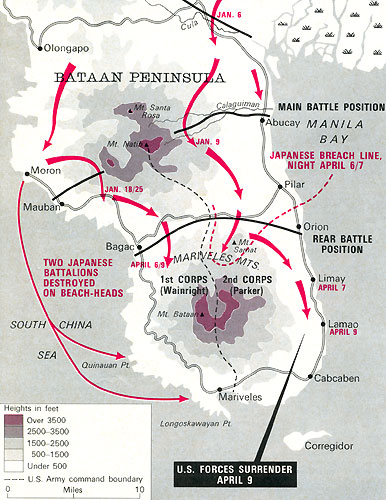

Bataan

Peninsula, Luzon Island |

Six Japanese advance

landings

The first landing on Philippine territory was made on the little island

of Bataan, about halfway across the strait separating Luzon from

Formosa. This was one of six advance landings planned for General

Homma’s XIV Army — the others were at Aparri and Vigan (on the north

and north-west coast of Luzon), at Legaspi (near the southern tip of

Luzon), at Davao on Mindanao, and at Jolo Island, between Mindanao and

Borneo. The immediate objectives were airfields from which fighters

could operate to cover the main landings which would follow. The

captured Legaspi base would be a threat to American reinforcements from

the south, and the landings at Davao and Job Island were designed to

secure advanced bases for a later move southwards against the

Netherlands East Indies.

The Japanese took a calculated risk in using quite small forces for

these first landings — the largest force was only a regiment. On Bataan

Island a Japanese combat naval unit of 490 men landed unopposed at dawn

on December 8. Two days later, Camiguin Island was seized, to provide a

seaplane base some 35 miles from Aparri.

Cautiously supported by strong naval and air forces, the Tanaka Force

(named after the commander of the II Formosa Regiment) approached

undetected, and landed 2,000 men at Aparri and Gonzaga, 20 miles

further on. The regiment’s other one and a half battalions, known

collectively as the Kanno Detachment, landed simultaneously at Pandan,

near Vigan, at dawn on December 10. Here the Japanese luck ran out: a

patrolling P-40 alerted the Far East. Air Force, and the remaining US

heavy bombers, with fighter escort, attacked the invaders’ convoy at

the landing area. The Japanese fighter screen failed to hold the

attacks, and two transports were damaged and beached. But the landing

was successful, despite rough seas and the air raid, and by the

following evening a small detachment had pushed 50 miles north along

the coast to occupy the town and airfield of Laoag.

With three airfields in their hands and no signs of a counterattack,

the Japanese commanders decided to move the entire regiment down the

west coast and join up with the main forces of the XIV Army that were

to land on the beaches of Lingayen Gulf. There were delays while

bridges were repaired and a light brush with Philippine troops at

Bacnotan was resolved, and Colonel Tanaka’s regiment arrived a few

hours after the main landings began.

The 3rd Battalion of the Philippine Army 12th Regiment was in the

Aparri/Gonzaga district, and quickly retreated south down the Cagayan

valley, offering no opposition. By the evening of December 12,

Tuguegarao airfield (50 miles inland) had been lost, and there was no

opposition by the Philippine Army at Vigan, and the nearest American

and Filipino force was that at Legaspi — 150 miles away. In south

Luzon, General Jones ordered road and rail bridges to be demolished,

and outpost defences prepared.

At 0400 hours on December 20, the Japanese landed at Davao. A

machine-gun squad of the 101st Regiment inflicted numerous casualties

until it was silenced by a direct hit from a Japanese naval gun. Nine

bombers from Batchelor Field, near Darwin, made a surprise raid on the

Japanese force collected to invade Job, but visibility was poor and

only near-misses were registered. Jolo fell on Christmas Day.

Within two weeks, General Homma’s advanced landing parties had occupied

airfields in north and south Luzon, in Mindanao, and Job. The Japanese

air forces had almost liquidated the Allied opposition, and the main

invasion troops were carried safely to the Lingayen beaches. Here the

main strength of Homma’s XIV Army began to disembark at 0500 hours on

December 22. The XLVIII Division, the IX Infantry Regiment, four

artillery regiments with 75-mm, 105-mm, 150-mm guns and 150-mm

howitzers, two tank regiments with 80/100 tanks, and a large number of

service and special troops were put ashore on the north coast of

Lingayen Gulf. Nevertheless, choppy seas, an attack by the Darwin-based

B-17s, and shelling from two 155-mm guns provided anxious moments for

General Homma and his staff.

Along the 20-mile section of the main Japanese landing strip ran the

all-weather Highway 3, which formed part of the road network that led

into Manila. South of the landing beaches and between the gulf and

Manila Bay, was the central plain of Luzon, a flat area of cleared

farmland with many towns and villages. Here — and on the beaches — the

Japanese had expected to find the main force of American and Filipino

defenders. Yet the only beach resistance was at Bauang, where a .50

machine-gun inflicted heavy casualties until the Japanese were able to

establish a foothold ashore. Then the defenders withdrew.

Colonel Tanaka sent a battalion to take the Naguilian airfield, and at

Agoo—at the southern end of the landing front—the XL VII Regiment,

supported by artillery, made a sweep inland to Rosario while the XLVIII

Reconnaissance and IV Tank Regiments came ashore and routed a battalion

of Philippine Army infantry.

Because of poor landing conditions (due to rough seas), General Homma

suspended unloading and disembarking operations during the afternoon,

and moved his transports further south to a point off Damortis during

the night; and the rest of Lingayan Force was thus ready to land the

next day — December 23.

On south Luzon, General Morioka’s incomplete XVI Division, numbering

7,000 fighting troops, landed at Siam and Antimonan on the narrow strip

of land between Tayabas Bay and Lamon Bay, and at Mauban, further

north. By the evening of December 24, the landing was complete, and the

only real resistance came from Philippine regulars at Mauban. Army

short-range fighter-bombers and aircraft from the seaplane-carrier

Mizuho gave close and deadly support to the Japanese troops who were in

control of the neck of the peninsula by nightfall.

With only a strong action on December 24 to delay them, the Japanese

had secured their initial objectives and had established a firm grip on

northern Luzon. They were now in a position to march south to Manila

along the broad highways of the central plain. Only the southern route

to the capital remained to be seized. And MacArthur knew that his

defence there was weak. He needed reinforcements and was relying on the

convoy of seven ships escorted by the cruiser Pensacola to bring in

troops, planes, and supplies. But the convoy failed even to test the

Japanese barrier of warships and aircraft, and a request by MacArthur

to have planes flown in from aircraft-carriers was turned down by a

navy which was now so sensitive to the situation that the submarines

were also evacuated. Torpedo-boats, minesweepers, gunboats, and tugs

were all that remained of the Manila Bay naval force. Marines and

sailors ashore were taken into the command of the army, and so too were

the remnants of the air force, while the few fighters left were hidden.

Appalled at the inability of the Philippine army to stand up to the

Japanese, General MacArthur announced on December 23 a plan for

withdrawal to Bataan. He planned to declare Manila an ‘open’ city after

he had moved his headquarters to the island fortress of Corregidor, and

the large quantities of ammunition and fuel which had already been

stored on the Bataan peninsula, were now augmented as small barges and

boats hastily carried more supplies from Manila to Corregidor and

Bataan.

By Christmas Day, 1941, when MacArthur moved into Corregidor, the main

defence line ran from near Binalonan—where the cavalry had made such a

good stand — along the other side of the Agno river and past Carmen to

the foothills of the Zambales mountains.

General Tsuchibashi’s infantry and tanks attacked the centre of the

defence line and soon moved through Villasis and crossed the river to

take Carmen by the evening of December 26. With the main road under his

control Tsuchibashi forced the Americans to use the railway to evacuate

the rest of the 11th Division, and Tsuchibashi’s troops then moved

quickly along Route 3 to intercept the train at Moncada but a road

block of three tanks and a 75-mm half-track delayed them, and the

Philippine infantry got through.

After the Americans moved back from their third to their fourth defence

line, extending from foothills to foothills across the 40-mile plain,

the Japanese XLVIII Division broke through at Cabanatuan, and both the

11th and 21st Philippine Divisions were forced into another withdrawal.

Aggressive artillery action by the Filipino gunners slowed down the

Japanese advance, but by December 31 General Homma’s troops were only

30 miles from Manila.

With the Philippine army forced back to Bataan, General Homma was

convinced that the campaign would now be brought to an early and

successful conclusion. Another Japanese general, Morioka, believed that

the ‘defeated enemy’ was entering the peninsula like ‘a cat entering a

sack’ — but he did not foresee the consequences of joining the cat in

the sack.

Against the line at Porac, Homma sent the IX Regiment, which penetrated

2,000 yards on January 2. The next morning, the Takahashi Detachment,

supported by 105mm guns, moved up to intercept an attack by a battalion

of 21st Division. The Japanese found the opposing infantry easy to deal

with, but withering fire from the Filipino artillery stopped the

Takahashi Detachment from causing a rout. On the marsh flank, the

Japanese advance was made along the highway, where fighting was

continuous and confused, infantry and artillery battling it out with

occasional use of tanks by both sides. The defenders continued to

withdraw, and the Japanese followed, harassing the retreating infantry

with small-arms and artillery fire. Then, from tanks forming a

road-block on the Lubao/ Sexmoan road, accurate firing cut some of the

Japanese columns to pieces. That night the attack was renewed across an

open field in bright moonlight, and again the American guns drove back

the Japanese; repeated attempts resulted in more heavy casualties.

As a result of the battering the Japanese had received, their fast

pursuit slowed down to cautious probing, while the Americans and

Filipinos crossed the Culo bridge at the Layac road-junction in a

confused congestion of vehicles, guns, and troops. Once again an

obvious target was ignored by the Japanese air force, and the Culo

bridge was blown up after the retreating army had crossed.

MacArthur realised that the Japanese success was achieved mainly

because of their superiority at sea and in the air, and although he

pleaded with his superiors for an Allied effort in the Pacific—the

first step would be to land an army corps on Mindanao — he accepted the

fact that relief was virtually impossible. He posted his defence across

the mountainous peninsula of Bataan and prepared for the final stand.

The first defense line on Bataan extended from the precipitous slopes

of the northern mountain, Santa Rosa, down to the sea on either side.

Wainwright had three reinforced divisions, the cavalry, and supporting

artillery in his 1st Corps on the left flank, and on the right Parker

had four divisions plus a regiment from the Philippine Division. Eight

miles behind was the rear battle position served by the PilarBagac

road. Preparing this line for a final defense was the USAFFE reserve —

the rest of the Philippine Division, the tank group, and a group of

self-propelled 75-mm guns. Corps and USAFFE artillery was emplaced to

cover the front lines as well as the beach defenses in all sectors.

Some 80,000 troops were now on Bataan and about 26,000 civilians had

also fled there. Food and motor fuel had been stored to satisfy the

requirements of 43,000 men for six months. Now there would only be

enough food for a few weeks. There was no mosquito netting and the

shortage of quinine tablets was already reflected in the number of

malaria cases admitted to the hospital. A few fighter aircraft were

miraculously still serviceable and engineers prepared fields for them

as well as helping the infantry and artillery to dig in.

The Philippine army was as ready as it could be, under the

circumstances, for General Homma to begin the battle.

A concentrated artillery barrage against 2nd Corps began at 1500 hours

on January 9. The defending guns replied effectively against the

attacking infantry. The II Battalion crossed the Calaguiman river and

managed to reach the cover of a sugar cane farm before midnight, where

they were only 150 yards from their enemy’s 3rd Battalion. While it was

still dark, the Japanese opened up with artillery and mortar fire, then

rushed out of the cane field in a screaming banzai charge in the face

of intense fire. As the leading men dived across the barbed wire coils

those following ran over their backs unimpeded, only to be shot down by

the defenders — and on the following morning, January 11, between 200

and 300 Japanese lay dead on the field, while the Philippine Army

Scouts, who had been rushed up from the reserve, were almost back to

their original line.

Colonel Takechi’s IX Regiment moved against General Parker’s left flank

to circle behind the Americans while pressure was maintained at the

other end of the line. Little headway was made and both sides suffered

heavy losses, yet the pressure was maintained again the following day

when

II Battalion attacked the 43rd Regiment. Artillery fire helped to

prevent the Japanese from gaining ground but the next day’s fighting

left them in possession of a hill between two Philippine army regiments.

Here, a counterattack took the Japanese by surprise and a Philippine

regiment pushed so far into their lines that the Japanese were almost

able to surround them. Attacked from three sides the Filipino troops

fled to the rear in disorder. Across the peninsula, Japanese attacks

against Wainwright’s 1st Corps successfully pushed them back to the

main defense line where fighting became intense. Beginning on January

18, it lasted until January 25, with both sides suffering heavy

casualties. One of Wainwright’s divisions was forced to escape along

the coast without rifles and in complete disorder. Disease and lack of

food were beginning to take their toll on the defenders as Japanese

pressure forced a general withdrawal, which began on January 23.

In a bold move to open up a front behind the main defense lines and

draw away infantry and artillery, two Japanese battalions landed at two

points near Mariveles at the tip of Bataan. At first contained in the

very rough country by a miscellaneous force of airmen, sailors, and

service troops, the two battalions were destroyed after three weeks of

bitter fighting.

But General Homma’s troops were running into more trouble as they

pressed against the last barricade — the Orion-Bagac line. With

American artillery shooting accurately from high positions, attacks

were costly; but even so they made several intrusions against the long,

thinly defended line. General Nara and General Kimura were both

successful in making deep penetrations which were then consolidated.

But then these strong pockets were gradually wasted by long, arduous

fighting in the rough country.

It was now Homma’s turn to withdraw and lick his wounds. By the end of

February, the XIV Army had suffered 7,000 casualties, including 2,700

dead, and between 10,000 and 12,000 were down with dysentery, beriberi,

and various tropical diseases. Homma could barely muster three

effective battalions — if the Philippine army had launched an offensive

at this time it could have recaptured Manila. But a lull settled over

no-man’s-land, and sections and platoons patrolled the area between the

lines, General Homma awaited reinforcements and the American generals

prepared for the final assault.

In Washington on February 8, the War Department received a startling

message from Philippine President Manuel Quezon, proposing that the US

immediately grant the Philippines their independence, that the islands

be neutralised, that American and Japanese forces be withdrawn and the

Philippine army be disbanded. At the same time General MacArthur sent a

supporting message to the Chief-of-Staff, General Marshall, explaining

that the Philippine garrison had sustained a casualty rate of 50%.

‘There is no denying the fact that we are near done,’ he added.

President Roosevelt repudiated the neutrality scheme, insisting that

the fight must continue. He authorised MacArthur to surrender Filipino

troops if necessary but forbade the surrender of American troops: ‘so

long as there remains any possibility of resistance.’ Meanwhile,

America and its Pacific allies had agreed to place MacArthur in command

of a new Allied HQ in the south-west Pacific. MacArthur had earlier

advised Marshall that he intended to ‘fight to destruction’ on

Corregidor. When commanded by his President and urged by his senior

staff officers, MacArthur accepted the proposed move. He left when the

fighting on Bataan had reached a stalemate. With him to Mindanao on

four PT boats went his wife and son, and the boy’s nurse, Admiral

Rockwell, General George (air force), General Sutherland, and 14 other

staff members. At Mindanao they were met by General Sharp who took them

to Del Monte airfield. In the early hours of March 12 the entire group

took off in B-17s and, at 9 am, landed safely at Darwin.

In his first public statement on reaching Australia, MacArthur said

that the relief of the Philippines was his primary purpose. ‘I came

through and I shall return’ he pledged.

General Wainwright was appointed the new commander of the Philippine

forces, and selected General King to command the Luzon forces on

Bataan. Here the most pressing problem was food: army-built rice mills

threshed the local palay; Filipino fishermen netted fish; horses,

mules, carabao, pigs, chickens, dogs, monkeys, snakes, and iguanas were

slaughtered; everything edible on the peninsula was harvested—but the

troops’ diet became more and more meagre. The absence of sufficient

vitamins resulted in outbreaks of beriberi, scurvy, and amoebic

dysentery, and malaria and dengue fevers spread with disastrous

rapidity.

Before MacArthur left he advised Wainwright to ‘give them everything

you’ve got with your artillery. That’s the best arm you have’. But on

Good Friday, April 3— which was also the anniversary of the legendary

Japanese Emperor Jimmu — it was General Homma’s guns, howitzers, and

mortars which opened up the final offensive.

Homma’s XVI Division and 65th Brigade had been reinforced with healthy

troops — the IV Division, arriving from Shanghai, and a detachment of

infantry, artillery, and engineers also reaching Bataan. Some 60

twin-engined bombers were flown in to Clark Field for a co-ordinated

air and artillery assault against the whole American line. The initial

objective was Mount Samat, a 2,000-foot rise behind the centre of the

Philippine army’s coast-to-coast defense line.

On April 3 the awesome bombardment began. For five hours the Japanese

guns, mortars, and howitzers pounded the sick and weary troops

defending the last few miles of Bataan. More than 60 tons of bombs were

dropped on the devastated line in front of Mount Samat. By evening, the

stocky brown men of 65th Brigade and IV Division had advanced 1,000

yards; the shell and bomb battering had made the preliminary move much

easier than Homma expected, so he repeated the formula the following

day, ordering his infantry to continue the attack without bothering to

consolidate the earlier gains.

Bombing attacks by the XXII Air Brigade were particularly successful on

April 4. By sheer chance the bombs fell among two battalions — the 42nd

and 43rd — who stampeded south for 4,500 yards, thus opening the centre

for the Japanese 65th Brigade, which pushed deeply behind Mount Samat

and threw fresh strength against the flank of 2nd Corps. By dawn on

April 7, the Japanese had pushed a bulge 4 miles deep into the centre

of the defenders’ line, and were commanding the heights of the northern

slopes of the Mariveles range.

General King planned to use a counterattack to stop the Japanese

offensive. The 45th Brigade, supported by a few tanks, attacked the

point of the bulge on the slopes of the Mariveles. But the attempt was

futile: there were no flanking attacks to support the brigade, and the

corps began to disintegrate. Whole units disappeared into the jungle,

communications broke down, and roads and trails became choked with

stragglers. Japanese aerial and artillery bombardment was maintained

over the whole front, concentrating whenever a stand was made—and as

2nd Corps retreated, 1st Corps became exposed to flanking movements,

and also withdrew.

General Wainwright could see that the rout could only be stopped by a

strong attack by 1st Corps against the Japanese 65th Brigade and IV

Division. He made this suggestion to General King but the Luzon

commander refused to issue the order, for he had only a disorganised,

routed, decimated, sick and demoralised army which would be slaughtered

piecemeal if he did not surrender it. It was his decision, therefore,

which ended the fighting on Bataan. On April 9, he sent two emissaries

forward with a white flag to meet the Japanese commander.

That night the ammunition dumps were exploded and some 2,000 people —

nurses, US army and navy personnel, some Cavalry Scouts, and other

Philippine Army troops — escaped in small boats and barges to

Corregidor.

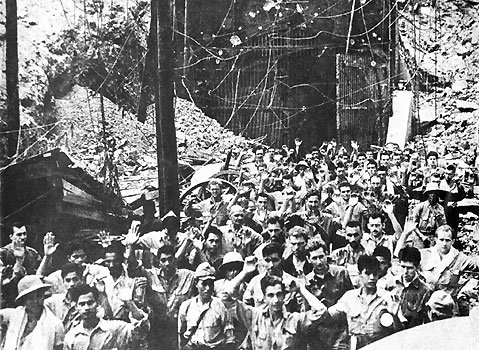

On Bataan, 78,000 men of the starved and beaten army went into

captivity. The conquerors concluded their victory by forcing their

captives into a ‘death march’, from Mariveles to San Fernando. With the

barest rations of food or water, the prisoners were forced to march the

65 miles under the hot sun, and many of them were clubbed and

bayonetted on the roadside — a vicious end to a vicious battle. Now

General Homma turned to the siege of Corregidor — the formidable

‘Gibraltar of the East’ — in order to claim possession of Manila Bay

and demand the capitulation of the whole of the Philippine Commonwealth.

|

|

Corregidor, ‘the Gibraltar of the East’, was

said to be invulnerable; but after the fall of Bataan, the fate of the

island was sealed. It could no longer be supplied, it could not ‘sail

away’, and hunger, disease, and incessant shelling had so weakened the

garrison that the final assault could not be resisted for long. With

15,000 troops on the island, the Americans were unable to find a

reserve capable of containing 1,000 Japanese.

When the 4th Marines at Bataan climbed aboard the barges and started

across the channel to Corregidor they were apprehensive about the trip.

They had heard a radio announcer in Manila tell the world, and

certainly the interested Japanese, that the Marines were making the

crossing that night. Previously, the 4th Marines had been stationed in

the International Settlement in Shanghai to protect American lives and

property, and in that capacity had many small clashes with the

Japanese. The Marines didn’t think that the Japanese would miss a

chance to take a crack at them while they were sitting ducks on the

barges.

‘You can’t bomb Corregidor,’ the radio announcer taunted them. ‘You are

afraid to bomb Corregidor.’ But the Japanese ignored the invitation and

the trip was uneventful. It was December 27, 1941.

Once ashore on Corregidor, the Marines began to gain a little

confidence in the invulnerability of the ‘Rock’. In their sweat stained

khaki, most of them unshaven, they stared in amazement at the military

police who met them at the dock at Bottomside. The MPs were in starched

suntan khaki, their shoes were spit-shined, and the brass on their

white belts was highly polished. Was there really a war on?

Electric trains whisked the Marines to the barracks at Middleside; and

as the guides escorted them to quarters, they saw soldiers playing

quietly at pool and billiards in comfortable orderly rooms. ‘What is

this,’ grunted a sergeant, ‘Wonderland?’

‘We’ll know for sure if Alice comes and kisses us goodnight,’

wise-cracked a private.

The next day Colonel Samuel Lutz Howard and his staff conferred with

Major-General George F. Moore, US Army, Commander of the Harbour

Defenses and the Fortified Islands of Manila Bay, on the strategic

deployment of the 4th Marines. The rank and file of the regiment were

left free to clean their weapons, shave, and wash clothes. That

afternoon they found the canteens and clubs were open and many slaked

their thirst and told sea stories over cold bottles of San Miguel beer.

As late as midnight, a dance band still played softly at the officers’

club.

By this time the Marines were convinced that the Rock was a pretty

solid place but they were still cautious. Several times during the day

the air raid warning sounded, and the Marines dutifully took cover —

much to the amusement and scorn of the regular garrison. Olongapo was

demolished, the Navy Yards at Cavite and Sangley Point in ruins, major

airfields and other military installations were bombed out of

existence; but the ‘Rock’ was invulnerable . . . so the soldiers said.

Their uncomplimentary remarks to the Marines, who continued to keep one

eye on the skies even while shooting craps and playing poker, caused

several small riots.

|

|

|

The

last Allied footholds off Luzon:

|

|

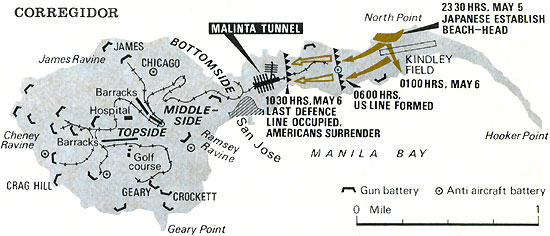

The defenses of Manila Bay were centered on the

"Gibraltar of the East", the island fortress of Corregidor; Fort Mills.

|

|

|

On the 29th, the Marines were given a briefing

on the harbour defenses by their company officers. Many of the

old-timers in the regiment had been stationed in the Philippines before

and had already circulated stories about the ‘Gibraltar of the East’.

The fabulous tunnels, the heavy armament, Fort Drum the concrete

battleship—all had been embellished with the purple prose of the master

raconteurs.

The harbour defenses in Manila Bay were made up of four forts built on

islands. Fort Mills was the island of Corregidor. Shaped like a

tadpole, it was 3 1/2 miles in length and 1 1/2 miles at its widest

point. Its head pointed towards the west, and its tail stretched

eastward; and at the junction of its head and tail, it was only 600

yards wide. This narrow low area was called Bottomside, and it

contained a small village, docks, shops and warehouses, the power

plant, and the cold storage plant. To the west of Bottomside the

promontory rose to a small plateau known, appropriately enough, as

Middleside. Here were the hospital and barracks.

Topside was another plateau, the highest point on the island. It had a

parade ground with officers’ quarters, headquarters, and barracks

grouped around it. The cliffs from Topside dropped to the sea; but

cutting into the cliffs were two ravines, Cheney Ravine and James

Ravine, which gave access from the beaches to the Middleside and

Topside areas.

The largest part of the tail end of the island was Malinta Hill and

under it was the most extensive construction on the island — Malinta

Tunnel. Its main tunnel, connecting Bottomside with the tail end of the

island, was 1,400 feet long and 30 feet wide. It had 25 laterals, each

about 400 feet long, branching out at regular intervals. Malinta ran

almost due east and west. A hospital was housed in its own set of

laterals and had an entrance facing north. The Quartermaster Corps had

another complex that went south and fed into the navy tunnel, which had

an entrance on the south side of Malinta Hill.

From Malinta Hill the island stretched out to the tip, at which point

the terrain was level enough to support Kindley Field, a small

airfield. There were 65 miles of roads on Corregidor and an electric

railroad with 13 1/2 miles of track.

On paper, the armament of Corregidor was awesome. Fifty-six coastal

guns ranging in calibre from 3 to 12 inches ringed the island. Two of

the 12-inch guns had a range of 15 miles and in addition there were six

12-inch guns with a range of 8 1/2 miles and ten mortars of the same

calibre. Nineteen other 155-mm guns could also reach out to 17,000

yards. In the anti-aircraft department there were 24 3-inch guns, 48

.50calibre machine-guns, and five 60-inch searchlights.

The main worry in the ordnance situation was the ammunition supply.

There was plenty of ammunition but little of it was of the type

suitable for attacking land targets, and there were no shells to

provide illumination for night fire. And what was really needed —

mechanically fused 3-inch high explosive shells for anti-aircraft

defense — was in short supply.

|

|

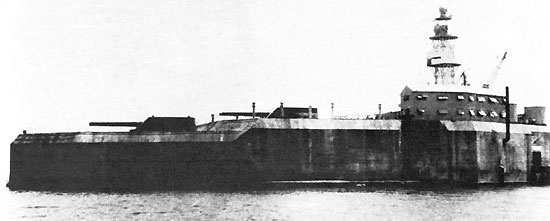

Fort

Drum, the concrete battleship. To build it, El Fraile Island had to be

shorn off, encased in concrete and armed with 14-inch guns. |

In addition to Fort Mills was Fort Hughes on

Caballo just south of Corregidor, a quarter of a square mile island

that rose to a height of 380 feet on its western side and armed with 17

guns ranging from 14-inch to 3-inch anti-aircraft; 4 miles south of

Hughes was Fort Drum.

To build Fort Drum, the engineers cut away the entire top of El Fraile

Island down to the water line; using the solid rock as a foundation,

they built a battleship 350 feet long and 144 feet wide with walls of

concrete up to 36 feet thick. USS Drum, as the sailors called it, was

armed with four 14-inch guns, four 6-inch guns, and antiaircraft

defense of three 3-inch guns. This brute was built to withstand

anything in the armament of the 1941 era.

The southernmost of the fortified islands was Fort Frank on Carabao

Island, only 500 yards from the shore of Cavite Province. Carabao rose

100 feet straight out of the sea and was armed with 21 guns ranging

from 14-inch to 75-mm beach defense guns.

In peace time the combined force on the fortified islands in Manila Bay

was under 6,000 men, most of whom were stationed on Corregidor. But the

war changed that. As the areas were bombed out, first came the

survivors from the Cavite Naval Base and then the troops from the

headquarters and service establishments in Manila. On Christmas Day,

General Douglas MacArthur established his headquarters there and with

him came a military police company, two ordnance companies, an engineer

company, and service detachments. By the time the 4th Marines arrived,

the island was crowded with men of all services, of several

nationalities, under a host of command structures.

On December 29 briefing was over for the Marines at about 1130, and

they milled about collecting their mess gear on the third and second

decks of the Middleside barracks where they were quartered. Some had

gone below and were having a smoke outside when the air-raid warning

sounded.

Prodded by their NCOs, the Marines moved to cover on the first deck of

the barracks running the gauntlet of the jeers of the headquarters and

service army billiard players.

There was a moment of silence, broken only by the click of the billiard

balls, and then the guns of the 60th Coast Artillery (AA) opened up.

The curious flocked to the windows and even to the rooftops to see what

was going on when the incoming flight of 18 twin-engined bombers of the

Japanese XIV Heavy Bombardment Regiment released its first load.

The saga of Corregidor had started.

Lieutenant-General Masaharu Homma was a practical soldier and a good

tactician. He did not believe that Corregidor was an impregnable

fortress, but his first task was to seize Manila and defeat MacArthur’s

army . . . Corregidor could wait. It could not slip away in the night.

Once Manila had fallen he issued his orders for an air attack on

Corregidor. Lieutenant-General Hideoshi Obata’s V Air Group (Army)

would strike at noon on December 29 ‘with its whole strength’, and an

hour later navy bombers of the XI Air Fleet would take over.

They were six minutes early. At 1154 the first flight, covered by 19

fighters, hit the ‘Rock’. They criss-crossed the island for half an

hour dropping 225- and 550-pound bombs. At 1230, 22 light bombers and

18 dive-bombers had their turn, and they were relieved by the navy.

Using about 60 aircraft, the Japanese continued the attack on the

island and shipping in the harbour for at least another hour.

General Douglas MacArthur’s USAFFE headquarters (United States Army

Forces Far East) were located Topside on the ‘Rock’ and he came out to

observe when the air raid sounded. He remained in a casual posture,

chomping on his cigar as the first wave released its bombs.

‘Get down, General, get down,’ an aide shouted. But the general

remained standing through another wave before his aide could convince

him to get in a staff car and go to Malinta Tunnel.

In the entire mêlée, the happiest men were those manning the

anti-aircraft guns of the 60th Coast Guard Artillery. They were in

action from start to finish in the 2k-hour air-raid. The cheers heard

by those huddled in the ground floor of the barracks and in the pseudo

air-raid shelters came from the gun crews as they shot down Japanese

planes. Three high-flying bombers were downed by the 3-inch guns, and

the .50-calibre batteries took care of four of the Japanese

dive-bombers.

But after the ‘All Clear’ sounded, the dazed non-combatants moved out

of the rubble of what was once ‘The Gibraltar of the East’, and started

to reorganise.

The island was in shambles. The first rack of bombs had smashed the

Officers’ Club, the vacated station hospital, and many of the other

wooden and corrugated-iron buildings from Topside to Bottomside. Other

bombing runs hit more important targets, but the results were the same.

Under the cloud of dust and smoke, Corregidor looked like one mass of

jagged and bent sheet iron. Before the dust had cleared, the troops

were organised and moved out to their combat posts. The bandsmen who

played at the officers’ club became stretcher bearers, and everyone on

the ‘Rock’ not assigned to a duty station in Malinta Tunnel started to

dig in. But everything was anti-climactic after the first air raid. It

was a routine of

‘get-bombed-dig-your-buddy-out-and-tomorrow-he’ll-dig-you-out’.

The bombers were back again on January 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6, dropping

their bombs from an altitude of from 24-27,000 feet. The anti-aircraft

batteries did yeoman duty.

To fire effectively at such extreme altitudes, men of the 60th had to

overcome many difficult problems. Only after the aircraft released

their bombs were they in range of the 3-inch guns. Men would stay at

their positions, tracking the attacking aircraft until the bombers were

directly overhead; then they would get in only four to six rounds

before the bombs hit the target area. These tactics demanded stern

discipline and iron nerves but the boys of the 60th had it. Battery

Chicago, for example, became so efficient even under these trying

conditions that its men ran up the almost unbelievable rate of 34

rounds per minute.

The 60th was credited with shooting down at least 25 aircraft during

this six-day period but the record does not tell the complete story.

The batteries kept the Japanese bombers flying so high they were

inaccurate in their bombing and many important targets, such as the

power plant and the pumping stations, survived.

For the rest of the month the ‘Rock’ enjoyed an uneasy rest from the

bombers for the Japanese V Air Group had left the Philippines. Life

turned into a dreary routine of digging in and looking for food.

It was at this time that the rumours started. Many of the men took

President Franklin D. Roosevelt literally when he announced: ‘Hundreds

of ships . . . thousands of planes . . . are coming to your rescue.’

Men waited for this dream convoy daily and in the sunset would climb to

a high point looking to sea for it.

A few learned the real score when a submarine carrying AA fuses arrived

from Hawaii in February. The working party unloading the submarine were

told about the tremendous damage the Japanese had inflicted on the

American fleet at Pearl Harbor. The propaganda radio station in Manila

played on this nerve factor by using a familiar American song as its

theme . . . ‘Waiting For Ships That Never Come In’.

Up to this point the ‘Rock’ had been spared from artillery tire; but

late in January a small Japanese artillery unit, under Major Toshinori

Kondo, had set up near Ternate in Cavite province just 12 miles from

Corregidor. Well concealed in valleys, his guns opened up on February 6

and continued to fire at one-minute intervals for three hours. Everyone

attempted but no one succeeded in—getting a fix on Kondo’s guns. They

did little damage and everyone soon got familiar with the new sound of

incoming artillery, but it was an ordeal.

While the shooting was going on, President Roosevelt worried about the

fate of Bataan and Corregidor; but in particular he worried about the

fate of MacArthur. The United States could not afford to lose its most

famous soldier; so on February 22, he ordered MacArthur to leave and

proceed to Australia. The general obeyed the order but waited until the

last minute and did not leave until March 12. When he left he turned to

General George Moore at the dock. ‘Keep the flag flying,’ he said, ‘I

am coming back.’

For the people on Corregidor, MacArthur’s departure seemed a ray of

hope. They knew that if anything humanly possible could be done to help

them, MacArthur would do it.

Major Kondo’s little guns had stopped firing; but in the middle of

March, Colonel Masayoshi Hayakawa and his 1 Heavy Artillery Regiment

moved into the Pic de Loro hills, much closer to Fort Frank. The I

Regiment was armed with ten of the most powerful artillery pieces in

the Japanese army—240-mm (9.4-inch) howitzers. With these brutes he

proceeded to clobber Fort Frank and Fort Drum. He did considerable

damage to Fort Frank but the 36 feet of concrete on top of Fort Drum

held magnificently. Each shell that hit would chip up at least 4 inches

of concrete; and living inside the concrete battleship was like living

in a steel barrel with someone pounding the outside. But the men and

the fort held up well.

On March 22 the Hayakawa Detachment pulled out and went to join the

final assault on Bataan. The forts of Corregidor had a short breather,

but on March 24 the bombers came back and General Homma had started the

last stage of his drive to take the ‘Rock’.

The attack came from 60 army and 24 navy aircraft. Using Clark Field as

a base, each plane could make three or four trips in the day so they

were able to start their attack at 0930 hours and kept it up until

1630. That night they came back for their first night raid of the

campaign, and for the next three days they continued the attack with at

least 50 bombers a day.

The raids did some damage but again it could be said that the gunners

of the 60th had saved the ‘Rock’. The Fort Mills power plant was still

intact; a few beach positions had been hit but casualties were light;

and Corregidor was still in fighting shape.

But now the food shortage was taking its toll. From January 1, the

troops had been on half rations.

‘The best meal we had,’ a soldier wrote, ‘was the day the bombs hit the

mule stables.’ In addition to the starvation, the quinine supply was

low, and the malaria rate high.

The men on Corregidor accepted the fall of Bataan stoically. They had

watched with awe the purple-green skies as demolition men blew up the

ammunition dumps and military installations on the mainland and knew it

was to be their turn next.

With the fall of Bataan, the Japanese had a straight shot at

Corregidor, just 3 miles across the north channel. They didn’t hesitate

to set up everything from 75-mm to their big 240-mm guns, all bearing

on Corregidor — the bullseye of the target. For the siege they

assembled the best in the Imperial Japanese Army: an Intelligence team

of 675 men with flash and sound gear; a squadron of observation planes

and a balloon company; 46 155-mm guns; 28 105-mm guns, and 32 75s; but

the weapons that were to do the most damage were Colonel Hayakawa’s

240-mm monsters. With the artillery team assembled and with the

observation balloon up, the duel started. Observers in the balloon were

able to pinpoint targets on Corregidor, by now stripped of protective

covering and camouflage, and direct battery fire into any and all

positions. It was an uneven fight.

The Corregidor batteries had some good days. Battery Geary dropped some

of its 670-pound mortar shells on a Japanese artillery concentration

destroying a battery, then another battery and an ammunition dump, and

finally on a group of tanks.

But when the big 240s started to slam back with their 400-pound

time-fused projectiles it was just a matter of time. Battery James

suffered 42 killed on April 15 when heavy fire collapsed a cliff over a

temporary dirt tunnel the batterymen had constructed. The men

suffocated before rescue teams could dig them out. Battery Crockett had

been hit, batteries Geary and Craghill were plastered as soon as they

opened fire. Only the 14-inch rifles of Battery Wilson on Fort Drum

were able to stay in action constantly.

April 29 was Emperor Hirohito’s birthday and the Japanese gunners

prepared a celebration. For several days they stockpiled their

ammunition, and on signal began the salute to their Emperor at 0725.

The din was terrific with the big guns firing almost — it seemed to the

dazed defenders — with the rapidity of machine-guns. The huge 240s came

in with a sound like tearing silk, and their tremendous detonations

literally picked the beach defenders up and threw them out of their

foxholes. Bombers attacked from overhead, but the men on Corregidor

didn’t realise that an air raid was going on at the same time — so

intense was the artillery fire.

By noon, fires had broken out all over the ‘Rock’ and exploding

ammunition dumps added to the danger of the artillery and bombing.

Jagged pieces of steel flew, trees were uprooted and hurtled through

the air, and solid rock cliffs were pounded into rubble until it seemed

that no living thing could exist on Corregidor.

The barrage continued for the next two days; then on May 2 the Japanese

intensified their fire: in a five-hour period they rained a total of

3,600 rounds on to the Geary/Crockett battery area. Finally one of the

time-fused armour-piercing 240 shells crashed through the weakened

concrete of a main powder magazine at battery Geary; and to the

Japanese in the observation balloon it looked like Corregidor blew up.

The defenders thought so too. As far down as Bottomside the concussion

was great enough to start men haemorrhaging through the nose and ears.

Several 13-ton mortars flew through the air like toy guns; one was

found on what was left of the golf course 150 yards away, and debris

mixed with unexploded 12-inch mortar shells came down all over the

island. Men staggered out of their foxholes after the smoke had settled

to start rescue operations, and it was fortunate the Japanese ceased

their firing operations for the day or the casualties would have been

trebled.

In the meantime, General Homma was having his problems. He had landing

craft for the final assault, but they were in the Lingayen Gulf or

Subic Bay area on the west side of Bataan. In order to move the landing

craft into the Manila Bay area, it was necessary to pass through North

Channel under the guns of Corregidor. After several feints during the

daylight hours, the necessary landing craft were brought down during

the night under cover of artillery fire.

Now the Japanese were ready. The Americans were tired, sick with

malaria—but ready to fight back after having lain in their foxholes

without a chance to fire back.

On the morning of the 5th, the Japanese opened up with everything they

had. But from Corregidor there was little answering fire: most of the

batteries were out of operation. By late afternoon, all wire

communications were knocked out, searchlights were put out of action,

land mines were detonated, machine-gun positions caved in, barbed wire

entanglements were torn up, and beach defences were in a hopeless shape.

‘It took no, mental giant,’ wrote General Wainwright, ‘to figure out

that the enemy was ready to come against Corregidor.’

Homma’s IV Division was indeed ready. The men had completed landing

manoeuvres, and thousands of bamboo ladders had been built to scale the

cliffs of Corregidor. The moon was to be full that night.

By 1830 hours, all the harbour forts were being pounded with the full

Japanese arsenal but then the concentration of fire went to the

island’s tail and to the beaches of the north shore. At 2100, with the

shelling growing more intense rather than slacking off as it usually

did with the approach of night, word went out from Colonel Howard to

bring all weapons out of cover and man the beaches.

Half an hour later the sound locators of the 60th picked up the sound

of landing barges being warmed up in the vicinity of Limay. The

Japanese were on their way.

It was a curious situation. The beaches were manned with a

heterogeneous group of Marines, soldiers, sailors, civilians, and

Filipino scouts, as ragged and bob-tailed an outfit as has ever been

gathered together in combat. Their armament ranged from Enfield rifles

to bomb chutes constructed to drop 30-pound air bombs on the beaches.

But few of the defenders had ever fired a shot in anger against other

troops.

It would seem that Homma’s well-trained IV Division would have no

trouble in going ashore against such a defence after the preinvasion

bombardment. But, even in the moonlight, the coxswains of the landing

barges were having trouble hitting their assigned landing areas. An

unexpected current, sweeping through the North Channel, drove the

landing force out of its assigned area to the tail of the island,

thousands of yards from their objective — Malinta Tunnel.

As they drifted sideways towards the east, fighting the current, the

beach defences took aim on them. They opened up with 75s, 37s,

machine-guns, and rifles. The defenders fired until the grease ran out

of their weapons, and the Japanese, who had been expecting an easy

landing, were shocked at their losses.

But at least 30% got ashore and established a beach-head. A few of the

barges, one carrying Colonel Gempachi Sato who commanded a unit of the

61st Infantry Regiment, slipped ashore unseen.

While the beach defenders continued to slaughter the second wave of

Japanese, Colonel Sato organised the survivors and started. his move

toward Malinta Tunnel.

The fighting that followed was so confused that no clear picture

emerges. Small groups set up strong points and defended them to the

death, but lack of communication among the defenders finally led to

defeat. As late as daylight the next day, some of the beach groups did

not know the Japanese had landed.

Colonel Howard didn’t learn of the landing until almost midnight, and

when he ordered his regimental reserve into action, it had trouble

getting through Malinta Tunnel into the zone of action. With 15,000 men

on Corregidor, 4,000 or 5,000 of them concentrated in Malinta Tunnel,

Howard and Moore found themselves unable to scrape together a reserve

capable of combating 1,000 Japanese. There were many administrators,

technicians, and commanders available, but what the ‘Rock’ needed at

this point was some fighters.

On the other hand, General Homma was biting his nails in frustration.

When he received the report that between half to two-thirds of the

landing craft had been destroyed, he felt there was a real danger that

his men might be driven back into the sea. Although he had 14,000 men

available he had only 21 boats left. When he heard that the Americans

were counterattacking. he went into panic.

However, the attack had not failed. Small detachments of the Japanese

had outflanked the American counterattacking elements, light artillery

had landed and was firing effectively in support, and they delivered

the final blow at about 1000 hours when they threw into action three

tanks which they had brought across.

Corregidor was finished. All reserves had been committed, all effective

guns were out of action, and the Japanese had a beach-head established

in force. At 1000 hours on May 6, General Wainwright had his aide

broadcast a surrender message to General Homma, and orders went out to

the troops to destroy their weapons. Corregidor, the ‘invulnerable’

fortress, had fallen.

The men on the ‘Rock’ reacted in many ways. Some got into the stores of

medical alcohol and got drunk, others got into the hoarded food

supplies and went on an eating binge, but most of them looked into the

future and wondered how long it would take MacArthur to come back.

|